by Peter Nicholson

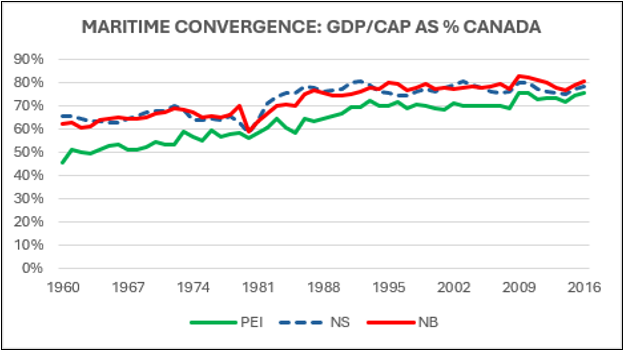

In terms of growth of GDP per capita, Canada’s Maritimes ranks at the bottom among US States and Canadian Provinces. But the story less often told is how much the Maritime Provinces have converged toward the all-Canada average over the long run. The chart below shows that PEI has gone from 46% of the Canadian average GDP per capita in 1960 to 75% in 2016, and likely higher since. Nova Scotia has converged from 65% in 1960 to 78%; and New Brunswick from 62% to 81%. (StatCan Table 36-10-0229-010). The catch-up was rapid through the early 1990s and has flattened since then, particularly for NS and NB. (Note that the convergence occurred despite major oil and gas development in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland & Labrador which gave a huge boost to those economies and thus also to Canada.)

This pattern is typical of long term economic growth trajectories where, following a period of GDP-level convergence, the growth rate of a lagging region or country eventually slows to match that of the “leader”. Thereafter the GDP level as a percent of the leader flattens and remains roughly constant. We see this relationship between the US and Canada—and indeed between the US and all the G-7 countries and several others as well. Germany, France, UK, Italy, and Japan all have GDP per capita levels of about 80% of the US (Italy and Japan a bit less). These ratios have been remarkably stable—with ups and downs reflecting particular domestic circumstances—since the 1970s.

The reason why advanced countries (and provinces in Canada) now all grow at about the same rate in per capita terms is due to the flows of investment, technology, ideas, and people among jurisdictions at comparable states of development. We may still ask why the catch-up process eventually stalls, usually at about 80% of the leader, apart from exceptional circumstances such as the resource bonanzas that have super-charged growth in, for example, Norway and Alberta?

I believe the catch-up phase eventually stalls out (after the low-hanging fruit has been picked) because it takes time for the innovations and investments that occur disproportionately in the economic leader—e.g., the US relative to the world and southern Ontario relative to Canada—to diffuse to, and be adopted by, everyone else. So long as the current leader continues to be the #1 innovator, the gap in per capita growth will not close. As to why catch-up appears to stall at roughly 80% of the leader—that is not well understood as far as I know, but presumably it reflects a number of structural factors that limit the rate of innovation diffusion. If in future the rate of innovation and investment diffusion were to speed up, the gap between the leader and the rest should narrow. Unfortunately, there is evidence that the rate of innovation diffusion from global firms at the technological frontier to the laggards has been slowing down. This also appears be the case within individual national economies, including Canada’s. If so, we would eventually expect to see a growing per capita GDP gap between the US and others in the G-7 and perhaps also between Ontario and the Atlantic Provinces.

The bottom line is that by far the most important driver of productivity growth is the rate of diffusion of innovation, technology investment, and business best practices from the global and regional leaders to the laggards. While it’s great to have a world-leading innovator in your country or province, these exceptional performers, by definition, will be relatively rare. What matters most is to have an economy that can rapidly adopt and adapt the best ideas and technologies from wherever they may have originated. Remember: an invention is not an innovation unless and until it spreads.